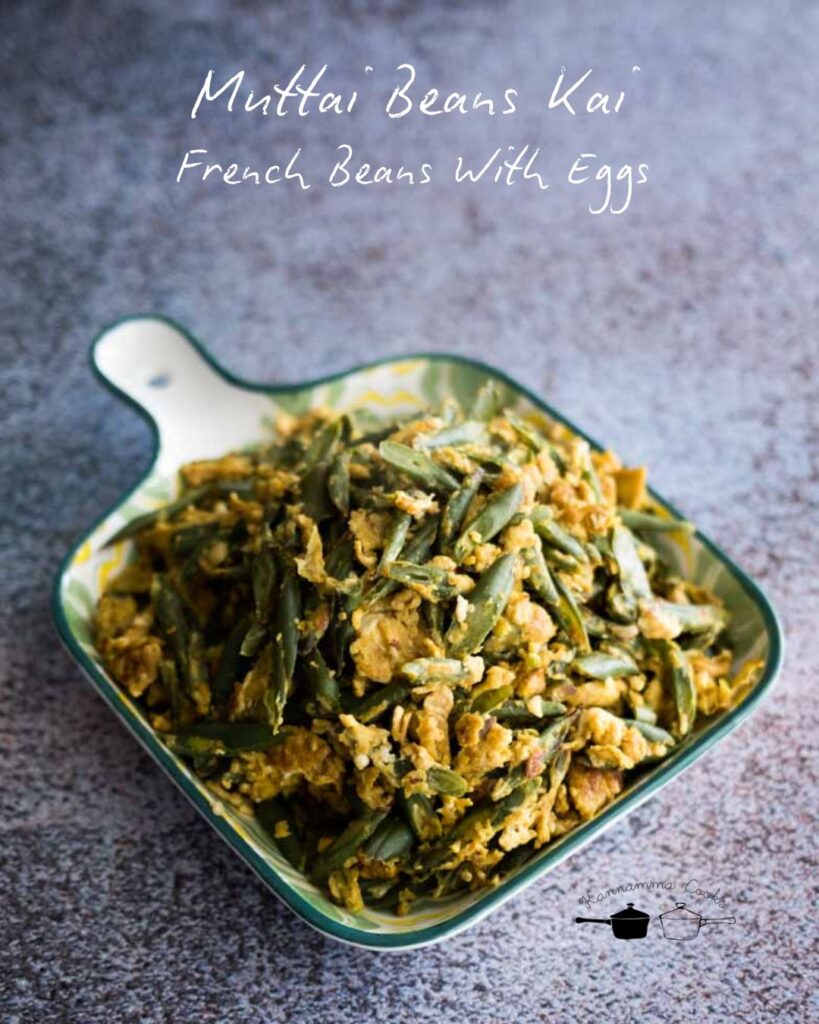

I truly enjoy the enthusiastic way Shankar shares his Sunday sapadu on his page . His vibrant storytelling, delicious recipes, and light-hearted moments with his team are always a delight. It’s not just food; it’s a full-on vibe that makes you want to cook, eat, and celebrate the everyday. 🌿🍛. When he posted this muttai beanskai recipe, I knew I had to try it—and I’m so glad I did! The oyster sauce adds a wonderful depth of flavor, making the dish hearty and satisfying. If you’re in Malaysia, don’t miss the chance to visit Shankar’s restaurant.

Now, coming to the recipe – it comes together in no time and makes for a perfect everyday dish. The only ingredient that’s a bit unconventional in a typical Tamil kitchen is the oyster sauce. I used the Kikkoman vegetarian oyster sauce for this version, and we absolutely loved it at home. Here is the link to buy – https://amzn.to/450BJAw

A non stick pan or a seasoned cast iron pan / wok is preferred for this recipe.

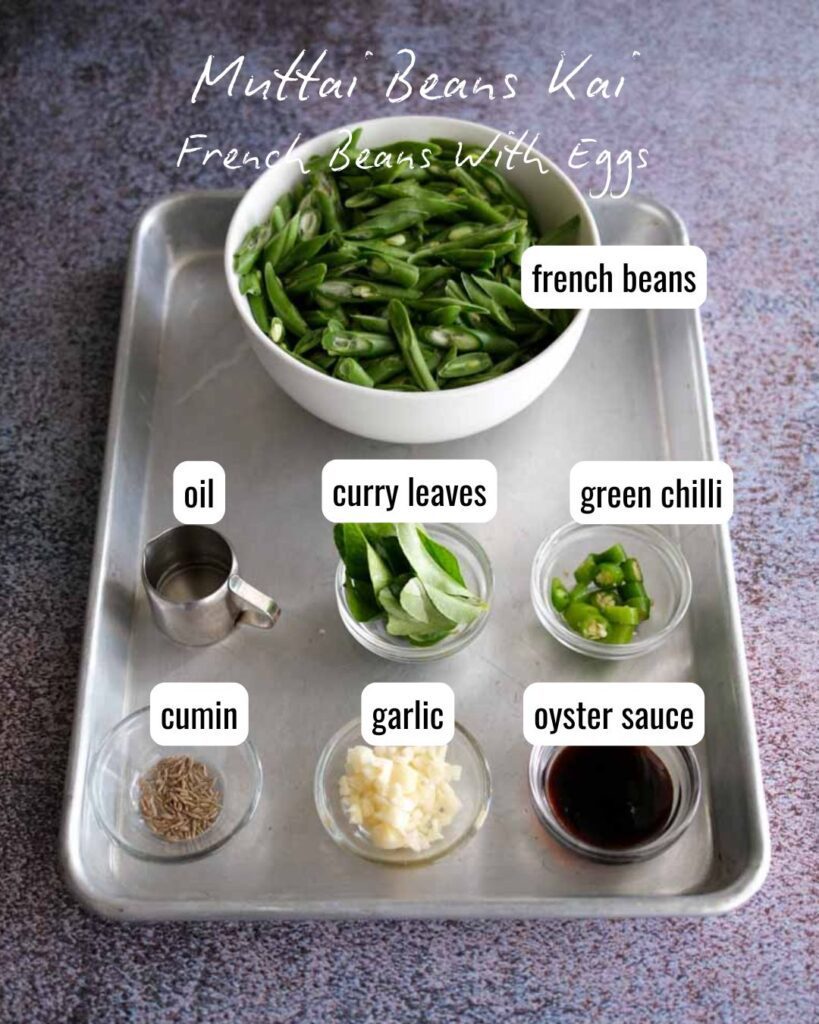

Here is what you will need for stir-frying the beans.

Heat a bit of vegetable oil in a pan. Add cumin seeds, curry leaves, chopped garlic, and green chillies. Sauté for a minute till it smells nice and fragrant. Now toss in the beans and mix well.

Cover the pan with a lid and let it cook on low heat for about 3 minutes.

Then open the lid, sprinkle a little water, and continue to cook for another 3–4 minutes. The beans should be cooked but still have a bit of crunch left.

Time for the flavour boost—add oyster sauce. I used the Kikkoman vegetarian oyster sauce here. It really brings a depth of flavour to the dish. Let it cook for a minute.

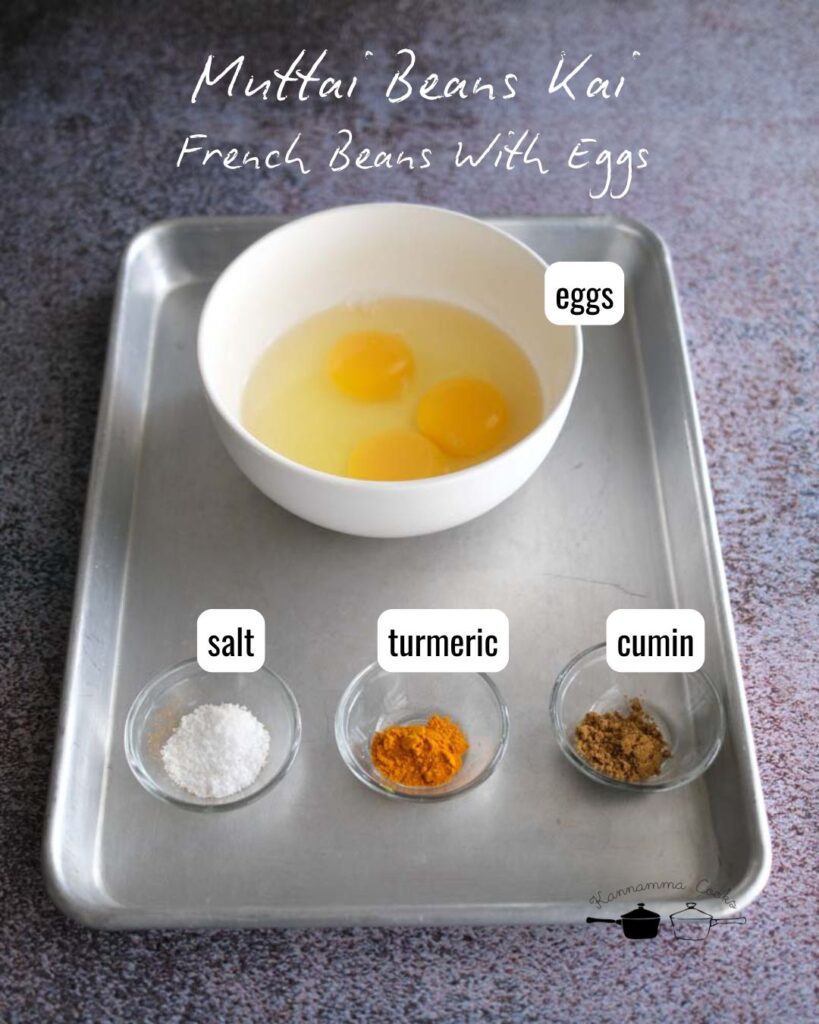

Prep the eggs

In a small bowl, mix salt, turmeric, and cumin powder with a splash of water to form a smooth paste. Instead of directly adding the spice powders to eggs, This little trick helps avoid spice clumps when you add them.

Crack the eggs into a bowl, add the paste, and whisk it all together.

Pour the eggs into the pan.

Don’t stir right away—let it sit for a minute so it sets a little. Then gently sauté everything together so the eggs cook through and coat the beans nicely.

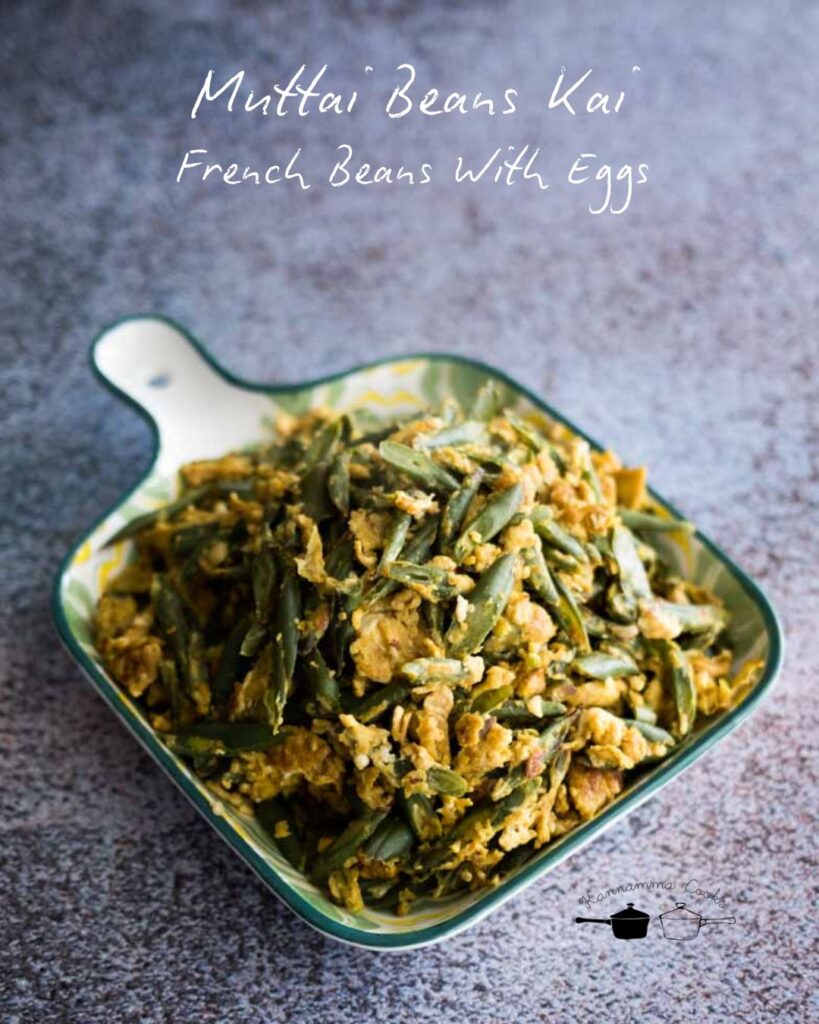

That’s it—muttai beanskai is ready! Serve hot with rasam or any kuzhambu for a comforting lunch.

For stir-frying the beans

For the eggs

For stir-frying the beans

Start by cleaning and prepping the beans. Slice them at a slight angle, about half an inch long, and set them aside.

Heat a bit of vegetable oil in a pan. Add cumin seeds, curry leaves, chopped garlic, and green chillies. Sauté for a minute till it smells nice and fragrant.

Now toss in the beans and mix well. Cover the pan with a lid and let it cook on low heat for about 3 minutes. Then open the lid, sprinkle a little water, and continue to cook for another 3–4 minutes. The beans should be cooked but still have a bit of crunch left.

Time for the flavour boost—add a spoon of oyster sauce. I used the Kikkoman vegetarian oyster sauce here. It really brings a depth of flavour to the dish. Let it cook for a minute.

To prep the eggs:

In a small bowl, mix salt, turmeric, and cumin powder with a splash of water to form a smooth paste. This little trick helps avoid spice clumps when you add them to the eggs.

Crack the eggs into a bowl, add the paste, and whisk it all together. Pour the eggs into the pan. Don’t stir right away—let it sit for a minute so it sets a little. Then gently sauté everything together so the eggs cook through and coat the beans nicely.

Muttai beanskai is ready! Serve hot with rasam or any kuzhambu for a comforting lunch.

- Author: Suguna Vinodh

- Prep Time: 15m

- Cook Time: 15m

For stir-frying the beans

For the eggs

For stir-frying the beans

Start by cleaning and prepping the beans. Slice them at a slight angle, about half an inch long, and set them aside.

Heat a bit of vegetable oil in a pan. Add cumin seeds, curry leaves, chopped garlic, and green chillies. Sauté for a minute till it smells nice and fragrant.

Now toss in the beans and mix well. Cover the pan with a lid and let it cook on low heat for about 3 minutes. Then open the lid, sprinkle a little water, and continue to cook for another 3–4 minutes. The beans should be cooked but still have a bit of crunch left.

Time for the flavour boost—add a spoon of oyster sauce. I used the Kikkoman vegetarian oyster sauce here. It really brings a depth of flavour to the dish. Let it cook for a minute.

To prep the eggs:

In a small bowl, mix salt, turmeric, and cumin powder with a splash of water to form a smooth paste. This little trick helps avoid spice clumps when you add them to the eggs.

Crack the eggs into a bowl, add the paste, and whisk it all together. Pour the eggs into the pan. Don’t stir right away—let it sit for a minute so it sets a little. Then gently sauté everything together so the eggs cook through and coat the beans nicely.

Muttai beanskai is ready! Serve hot with rasam or any kuzhambu for a comforting lunch.

- Author: Suguna Vinodh

- Prep Time: 15m

- Cook Time: 15m

Find it online : https://www.kannammacooks.com/muttai-beanskai-french-beans-with-eggs/

If you’ve ever clicked around for that perfect rasam or a hidden way to roast idli, you’re not alone. Across kitchens in Chennai, Coimbatore, and beyond, enthusiastic home cooks are quietly embracing anonymous recipe hubs —digital spaces where traditions are shared freely, without oversharing personal profiles or reinventing the wheel.

These hubs aren’t exactly mainstream websites. They often exist as shared Google Docs, Discord communities, or encrypted message threads where members post old family recipes for vindaloo masala, pachai manga kulambu, or brittle coconut candy—arising from nostalgia, trust, and an appreciation for anonymity.

In a digital world increasingly dominated by branding, influencer content, and ad monetisation, these quiet corners of the internet are helping preserve culinary authenticity. Interestingly, the same privacy-first approach can be found in completely different areas—like digital platforms built for anonymous experiences , where privacy isn’t a feature but the foundation. The mindset is similar: people want meaningful access, not more identity exposure.

The Allure of Anonymous Recipe Sharing

Why cook from published blogs when you can access a grandmother’s dosa batter proportions passed down discreetly? Many traditional recipes don’t make it to public platforms, either because families guard them closely or because they don’t translate well into SEO snippets.

What cooks find appealing about these hubs is their authenticity. You won’t encounter clickbait headings like “5‑minute vada fix” or “Celebrity masala secrets.” Instead, expect honest instructions: soak urad dal overnight, grind only with a pinch of salt, ferment in a steel utensil for 8–10 hours—no frills, no fluff.

How These Hubs Operate

Most anonymous cooking communities operate on platforms like Google Drive or Telegram. Members share recipes via pastable text or scanned handwritten notes. A few admins maintain order. Permissions are often request-based; you respond to a brief bio and maybe a favourite dish. Once you’re in, it’s culinary freedom.

A recent story published by SBS Food detailed how a community of South Indian cooks shared generations-old rasam recipes across encrypted channels—without publishing their names, locations, or photographs.

Why This Works for Regional Recipes

South Indian cooking often relies on intuitive measurements—”a lemon-sized ball of tamarind” or “a whisper of hing.” That cultural context often gets lost in the world of standardised, Western-style cookbooks or blog formats.

But in anonymous hubs, nuanced questions get fast, relevant answers. Need your sambar to match what your thatha used to make in Madurai? Chances are someone has a tip like: “Use toor dal from Pollachi and roast the methi seeds before grinding.”

Cultural Preservation in Every Chat

It’s not just about food—it’s about context. Alongside recipes, members share lore: how appa preferred coconut oil for vengaya sambar, or how a banana-leaf thali is plated for Aadi Perukku. These details ground recipes in culture and memory.

In a fast-changing India, that kind of documentation is invaluable.

Privacy as Respect, Not Secrecy

These communities don’t avoid names because they’re secretive. They do it out of respect. Nobody’s looking for fame or clicks. The recipe is the star—not the chef.

In fact, that mirrors trends in other private-first communities. People are slowly shifting to platforms where data isn’t currency, and value is measured by quality—not reach. Whether you’re sourcing ancestral chutney recipes or seeking a safer space to engage online, this ethos resonates deeply.

What Food Bloggers Can Learn

Mainstream culinary sites—especially those focusing on regional cuisine—can benefit from observing how these hubs operate. We’re talking about:

- Emphasising clarity over clickbait

- Respecting cultural accuracy (e.g., calling something ‘Puliyodarai’ only when it truly is)

- Documenting traditions, not just ingredients

Some legacy platforms like Tarla Dalal’s online archive have maintained this balance by documenting regional meals without diluting them for mass appeal.

Starting or Joining a Private Recipe Hub

Interested? Here’s how to begin:

- Choose a niche (Tamil Brahmin cuisine, Andhra podis, etc.)

- Start with friends or family cooks who can contribute

- Use simple tech: Google Drive folders, WhatsApp groups, or email chains

- Keep it balanced: share if you expect to receive

- Honor the code: no republishing recipes outside the group

The Future of Regional Cuisine Is Quietly Collaborative

As India’s food identity gains global attention, there’s a parallel movement back home to keep it grounded. These anonymous recipe circles may not show up on search engines—but they’re preserving taste, memory, and method in ways that public platforms often cannot.

That’s why more South Indian home chefs are logging out of the algorithm—and logging into communities built on respect, culture, and flavour.